Books I Read in May

Unless, by Carol Shields. Long ago I read The Stone Diaries (which won the Pulitzer Prize), my only Shields novel until now. Which is too bad, because Unless is a wonderful novel. In an uncanny way, Shields strikes me as a bridge between tell-nothing-about-the-narrator Rachel Cusk and allow-us-fully-in Elizabeth Strout, not to mention that all three novelists are writing books about women who are writers (something which did not occur to me until I’d finished all three books, which you can take as proof of my obtusity). Set north of Toronto, Unless charts both the writing life and the mothering life of Reta Winters, whose beloved oldest child, in an abrupt turnaround, spends her days on a Toronto corner with a begging bowl, seeking goodness. The daughter’s mysterious malady and her mother’s heartbreak are charted in one of the most quietly fierce feminist novels I’ve read. Beautiful.

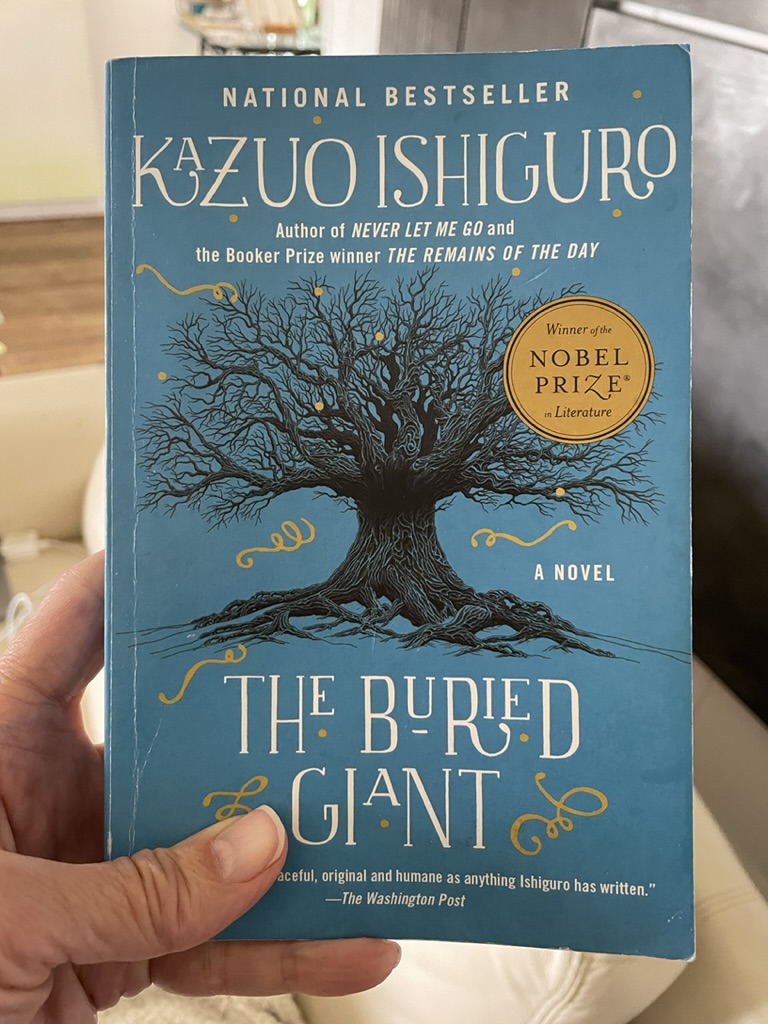

An Artist of the Floating World, by Kazuo Ishiguro. I space my Ishiguro novels out, mostly because I don’t want to run out of them in my lifetime, and I picked up this one at Magers & Quinn fully intending to save it for later, but then read the first page and boom, finished it. I have come to understand there’s a central mystery at the heart of all Ishiguro novels, one that will be revealed to me slowly, in small bits and fragments of narrative and dialogue, and that by the end will have torn my heart open. Such is the way with An Artist of the Floating World, Ishiguro’s second published book. Set in Japan in the first few years after WWII, an older artist, paying close attention to those around him, begins to rethink his role, both personal and public, in his country’s march to war. A quiet, introspective, profoundly human book.

The Corrected Version, by Rosanna Young Oh. In this collection of poems, Oh reflects on a childhood as the daughter of Korean immigrants who opened a small grocery store on Long Island. From the future she lives in now, Oh looks back on the details of her family’s life, and what her parents taught her in word and example as they devoted themselves not to the work of the mind they’d been educated for, but to the labor of keeping the store and their children going. The poet’s eye Oh brings to scene and imagery turns memory vivid, infused with both love and clarity. From my favorite poem, in which she and her father are picking through blueberries: Suddenly, my father’s voice emerges as though from a / distance: “You were not meant to live this kind of life.” / But nor was he—a man with a mind made wide by books,/who as a child rose with the sun to read by its light. To me, born and raised in a nation where most inhabitants, like me, are descended from immigrants, this lovely book feels both familiar and deeply specific.

Useful Phrases for Immigrants, by May-Lee Chai. Short story collections can be hard for me, only because each story often feels novel-like in its depth and scope, and then poof, it’s over and there are many more to read. Not so with Chai’s stories, which are similar (sometimes puzzlingly so; family configurations and objects can be startling alike, especially in two of the stories) – I read the collection in a single day. Chai is piercingly honest and evocative in her exploration of the Chinese immigrant experience, both recent (xìa hai, jumping into the ocean) and generational, in long-established families. In this way, Useful Phrases for Immigrants reminds me of Kelly Yang’s wonderful novels for children; I was equally absorbed in Chai’s people and their frustrations, accomplishments, longings, and relationships both familial and cross-cultural. I wish that Chai’s fictional Uncle Lincoln, who radiates kindness and clarity, existed in real life, so that we we could be friends.

Horse, by Geraldine Brooks. This is my first novel by Pulitzer Prize winner Brooks, and…wow. I learned so, so much about the world of horses, horse racing back when it was a national obsession, and aspects of the Civil War I hadn’t known about. Horse skips back and forth from mid-1800s Kentucky and points south to 2019 D.C. to 1950s Manhattan, and is mostly told through the voices of Jarret, an enslaved horseman; Thomas, an equestrian artist; Martha, a mid-century pioneer contemporary art collector; Jess, a scientist who specializes in articulating the skeletons of long-gone animals, and Theo, finishing his Ph.D. in art history. I list these voices because they all seem so different from one another, and yet part of Brooks’ genius is weaving an increasingly intimate net that enfolds them all –and us—in the historical and ongoing racial wrongs of this country and the world. Jarret is (to me) by far the most affecting person in this exceptional, extraordinarily researched novel.

Maniac Magee, by Jerry Spinelli. Another in my never-read-this-children’s-classic when it came out books. What an interesting, unusual, challenging book. Jeffrey Magee, aka Maniac Magee, takes off running (literally) in the first few pages and never stops. Set in a Pennsylvania town divided (again literally) into Black and white halves, Maniac takes it upon himself, in his search for a home and family to call his own, to unite the townspeople. The book is unrealistic and yet, in what feels like an absolute determination toward happiness and resolve, transcends that unrealism to become a story of optimism, belief that change can happen, and love. Somehow I wasn’t fundamentally put off by the fact that it’s a white kid written by a white author who opens up hearts on both sides of the divide. I ended up loving everyone in this book, which, I noticed only after finishing it (see obtusity comment above), is another Newbery winner.

Ivy and Bean, by Annie Barrows and Sophie Blackall. I found this wee book, the first in the beloved series, in a little free library and gobbled it down as I drank a mug of coffee (I drink coffee slowly). Such a charming, funny, spirited novel. I kept thinking all the way through of how much fun my friend and I had writing the Bink & Gollie books together, and the effervescence of Ivy and Bean, both in the evocation of the two kids and in the pairing of text and illustration, made me think that Barrows and Blackall must also have so much fun writing and illustrating these books. A charmer.

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Ugly Truth, by Jeff Kinney. I remember reading and enjoying the first Wimpy Kid when it came out long ago. Either I’ve changed or the books have, because I didn’t just enjoy The Ugly Truth, which was published a few years later, I sat on my porch chortling out loud all the way through. Kinney is so, so good at being inside the head of a middle school kid, and so is the way he relays family, school, and social situations. The diary format is perfect because it allows the reader to feel and empathize with child narrator Greg’s point of view while also stepping back and viewing him from an outsider’s point of view. Nothing is off-limits for discussion, and yet there’s something so reassuring in the way everything is discussed. I finished The Ugly Truth and texted a friend: “Kinney’s a damn genius.” Truth.