Books I Read in June (with mini-reviews)

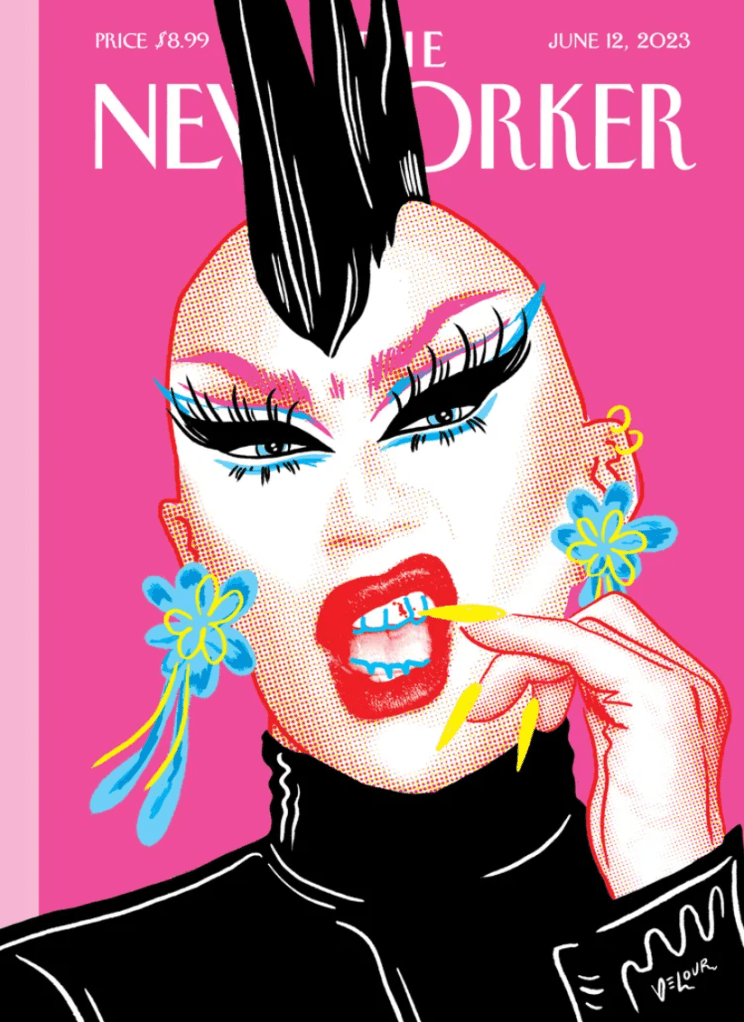

The New Yorker, 12 June 2023. If you are like me, and I’m sure you’re not because you’re much better and more organized, sometimes the New Yorkers pile up. And up. And more up. And oh look, a new one just came sailing through the mail slot. In order to make myself (and possibly you?) feel like less of a loser, I hereby declare each issue of the New Yorker a book in and of itself, because when I put it that way, reading each New Yorker book becomes a beautiful endeavour (I purposely stuck that “u” in endeavour because of my love and admiration of Canadians). The June 12 issue is my favorite issue of the month. In it, Jiayang Fan, a writer I greatly admire, writes about her mother in What Am I Without You? This is Fan’s first piece of memoir in the wake of her mother’s death, of ALS, and in my view it’s the best thing she’s written yet. Wild. Poetic. In it, Fan states that because of the circumstances of their you-and-me-and-nobody-else shared life, she and her mother are not separate people; they merged into a single being in both life and death. I don’t know many writers who would make that claim with such unapologetic clarity. That cool fierceness is one of the things I most admire about Fan.

Ordinary Time, by Kathleen Wedl. In this, the poet’s debut collection, threads from a lifetime of marriage and family and fifty years as a psychiatric nurse are woven together into a portrait of love and wisdom. Wedl understands that the things, the literal things we draw around us in our lives, are evidence of our longings and our loves, and she is at her poetic best when describing, with trademark deadpan humor, the give and take of a long marriage of opposites: You give me Honeycrisp/I give you prickly pear. You give me Brave New World/I give you Great Expectations. In my favorite of all the poems in this lovely collection, she looks back on the years when her granddaughters sprawled out in her non-allergenic sealed space of a bedroom, with their pollen infested ripped shorts/and indoor/outdoor socks, thinking of all that she wished away, those long afternoons/all breathable air saturated with happy/chittering and chortling. So often we don’t know we loved something, or some time, or someone so much when we had them. Lovely work.

The New Yorker (again), 12 June 2023. Like so many others, I love, revere, and seek out the work of George Saunders. His latest story, Thursday in the same issue of the New Yorker as Jiayang Fan’s stunning What Am I Without You? is another Saunders story that starts out …weird? is that the word? and gradually deepens and deepens until, if you’re me, you get to the end, heart cracked and bewildered, and have to put the magazine down and take your dog on a long walk, trying to find your way out of Saunders World back into your own life while also trying to figure out just how the man does what he does. Damn.

These Walls Are Starting to Glow, by Karen Bjork Kubin. My expectations of this chapbook, based on previous experience of the poet’s beautiful work, was that it would be a hushed, inward, collection of lyrical poems that draw their power from language, artistry, and the wisdom that comes from hard-won experience. So I propped myself up on the orange couch on my pretty, sunlit porch, opened up to the first poem and…holy shit. I sat there in shock. Wild, fierce, full of fury at the cruelty of those in power and an equally furious determination to make this world better, these poems Take A Stand. Each poem begins with an epigraph from a traditional nursery rhyme about a girl or woman and then flips that narrative on its head. I read the entire chapbook in one sitting. Are you looking for a gift for someone you love, maybe someone young, someone questioning the crazy unfairness of this world? Give them this book.

Enormous Changes at the Last Minute, by Grace Paley. Paco the dog-child and I were out for one of our early morning rambles when we stopped by one of our favorite Little Free Libraries to inspect its contents. I saw a copy of Enormous Changes and thought, huh, it’s been many a year since I read a Grace Paley story, and I’ve never read the entire collection; perhaps it’s time. Long, long ago I read stories by both Paley and Tillie Olson at the same time, and their influence on me has been silent and deep. (I read Olson’s work with fascination and unease as a young woman born with a ferocious determination to be a writer; they read as if she were trying to tell me something about being a woman in this world, a woman with a marriage and children and housework who wanted all that and who also wanted so much more, and about how hard I would have to work to stake my claim on tough, unyielding ground. She was right.) Meanwhile, Grace Paley is a wild writer, an experimentalist icon whose stories startle and fascinate me now way more, somehow, than they did when I was young. These are daring stories in every way, from subject matter to language, and it stuns me that they were published more than fifty years ago. Structurally and in terms of voice and point of view, these stories read as if they’re inside out, almost, in that you don’t always know if you’re inside the narrator’s head or if she’s speaking. Paley is fearless, with a voice that reads to me like the precursor of Elizabeth Strout’s Lucy Barton. And she’s also disturbing, with “disturbing” meant here as a kind of troubling and exhilarating compliment.

Takedown Twenty, by Janet Evanovich. You know I’m a Stephanie Plum fan who turns to her shelf of closely guarded Stephanie novels when I need a break from the world. One of these novels goes down just like my twice-yearly bag of Lay’s classics. You end up full and satisfied and you know you won’t need another one for some time. Thank you, Stephanie Plum, Lula, Ranger, Morelli, Grandma, Giovichinni’s, Cluck in a Bucket, dear departed Uncle Sandor and your giant powder-blue Buick, and everyone who lives in the Burg. Sometimes you’re just the ticket.

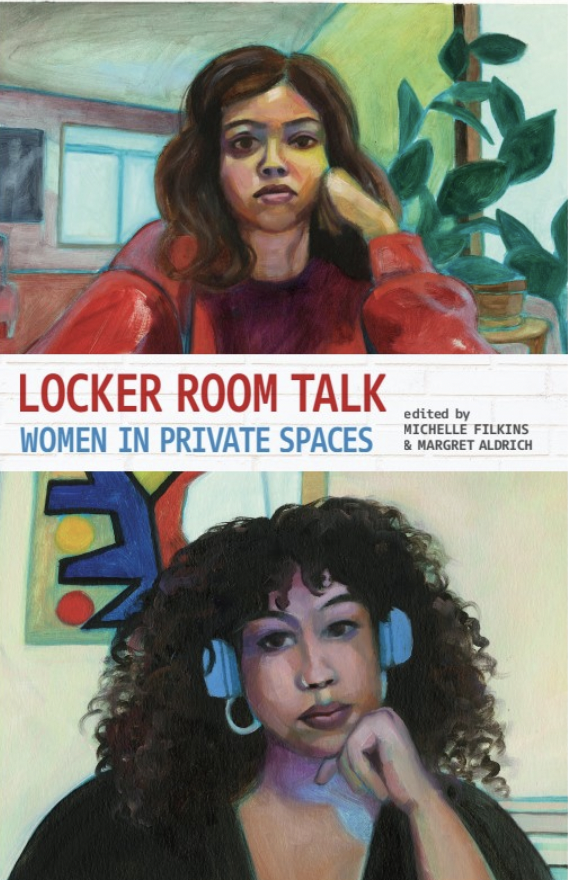

Locker Room Talk: Women in Private Spaces, edited by Michelle Filkins and Margaret Aldrich. Locker room talk. A familiar phrase turned hideous to so many of us by what it now evokes in the wake of the 2016 election. In this absorbing and wonderful anthology, just out from Spout Press, editors Filkins and Aldrich reclaimed the phrase by asking women writers to contribute essays and poems and memoirs about what “locker room talk” means to them. I was moved to tears by some of the contributions, include Jude Nutter’s poem about a brief, piercing airport encounter, Maureen Aitken’s memoir about the freedom of dancing in the singular bar where she felt safe, Mo Murphy’s lovely piece about all she’s learned and held in her heart in decades of work in a salon, and several others. This is a beautiful book. (Full disclosure: I have an essay in this anthology.)