Poem of the Week, by Dorianne Laux

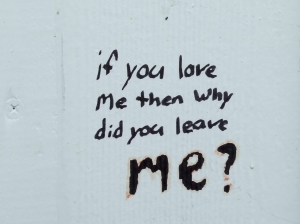

The suicide of Alan Krueger last week, a man I didn’t know but whose work I admire, a man clearly beloved by so many, hit me hard. It brought me back to my early twenties, when the suicide of someone I loved both ended his life and permanently altered mine. Crying comes hard to me and does not bring relief, but it came anyway this week. At one point I found myself alone, apologizing out loud for things I wish I’d done differently.

The suicide of Alan Krueger last week, a man I didn’t know but whose work I admire, a man clearly beloved by so many, hit me hard. It brought me back to my early twenties, when the suicide of someone I loved both ended his life and permanently altered mine. Crying comes hard to me and does not bring relief, but it came anyway this week. At one point I found myself alone, apologizing out loud for things I wish I’d done differently.

I’m haunted by the sense that the cruelty and hatred so on display these days made things worse for Alan Krueger. It makes things worse for everyone. The only thing I can do, like the poet below, is try to subvert it with kindness.

For the Sake of Strangers, by Dorianne Laux

No matter what the grief, its weight,

we are obliged to carry it.

We rise and gather momentum, the dull strength

that pushes us through crowds.

And then the young boy gives me directions

so avidly. A woman holds the glass door open,

waits patiently for my empty body to pass through.

All day it continues, each kindness

reaching toward another – a stranger

singing to no one as I pass on the path, trees

offering their blossoms, a retarded* child

who lifts his almond eyes and smiles.

Somehow they always find me, seem even

to be waiting, determined to keep me

from myself, from the thing that calls to me

as it must have once called to them –

this temptation to step off the edge

and fall weightless, away from the world.

*Note that this poem was published in 1994, when this word was in common usage.

For more information on Dorianne Laux, please check out her website.

A few days ago at sunset the sky was unearthly. The Painter came home, grabbed his camera and tripod and headed to the beach to take a bunch of photos. My internal, unspoken take on this, having never seen him take a sunset photo before: You had a frustrating day in the studio. Nothing was working with your paintings. You feel blocked, so you’re trying something new, to change up the energy and get things moving again.

A few days ago at sunset the sky was unearthly. The Painter came home, grabbed his camera and tripod and headed to the beach to take a bunch of photos. My internal, unspoken take on this, having never seen him take a sunset photo before: You had a frustrating day in the studio. Nothing was working with your paintings. You feel blocked, so you’re trying something new, to change up the energy and get things moving again.  We were classmates. He was a country kid, like me, and like me, he was condemned to ride the bus for miles and miles. I dreaded that bus every day of my life –it was a place of fear and intimidation and endless cruelty.

We were classmates. He was a country kid, like me, and like me, he was condemned to ride the bus for miles and miles. I dreaded that bus every day of my life –it was a place of fear and intimidation and endless cruelty.  My daughter at eight: What would happen if you die? I tell her she would be very sad but everyone would take such good care of her, and she says No, they wouldn’t. Because I would be dead too, of sadness. My son at four shuffles out of the bedroom in his first pair of flip-flops, having put them on himself with the strap between his second and third toes. It’s fine, mama, don’t worry, they don’t hurt, I can walk. My grandmother, flustered and red-faced in the small kitchen where she’s trying to make dinner for me: Oh Alison, I’m just no use at all anymore. Me outwardly protesting but inwardly stricken by the knowledge that in that single instant, everything is now changed.

My daughter at eight: What would happen if you die? I tell her she would be very sad but everyone would take such good care of her, and she says No, they wouldn’t. Because I would be dead too, of sadness. My son at four shuffles out of the bedroom in his first pair of flip-flops, having put them on himself with the strap between his second and third toes. It’s fine, mama, don’t worry, they don’t hurt, I can walk. My grandmother, flustered and red-faced in the small kitchen where she’s trying to make dinner for me: Oh Alison, I’m just no use at all anymore. Me outwardly protesting but inwardly stricken by the knowledge that in that single instant, everything is now changed.  The day after I moved to Minneapolis, I bought a sewing machine. This was in the days of newspaper ads, and I found a used one for $60 and insisted my then-boyfriend and I track it down that very day. That ancient, impossibly heavy machine is what I’ve used to make all the quilts I’ve ever made, sewing together blocks I hand-stitch piecemeal. Story quilts, every one of them, made not according to a pattern but out of my head and heart.

The day after I moved to Minneapolis, I bought a sewing machine. This was in the days of newspaper ads, and I found a used one for $60 and insisted my then-boyfriend and I track it down that very day. That ancient, impossibly heavy machine is what I’ve used to make all the quilts I’ve ever made, sewing together blocks I hand-stitch piecemeal. Story quilts, every one of them, made not according to a pattern but out of my head and heart.  My three children and I were in upstate New York. This was a long time ago, and we were making our annual summer trek around New England to visit family and friends. We had just finished touring the Utica Club Brewery, one of my favorite childhood destinations, a tour that ends with a complimentary beer or root beer in a Victorian saloon. We were all tired. I was chatting with my parents while my children wandered around, trying out various red velvet chairs.

My three children and I were in upstate New York. This was a long time ago, and we were making our annual summer trek around New England to visit family and friends. We had just finished touring the Utica Club Brewery, one of my favorite childhood destinations, a tour that ends with a complimentary beer or root beer in a Victorian saloon. We were all tired. I was chatting with my parents while my children wandered around, trying out various red velvet chairs.

names and roles taken directly from a seriously cheesy VHS TV series called Ewoks (which I probably found for a quarter at a garage sale). What I remember most is my daughter’s bright eyes as she tromped around the house after her older brother, who was always kind to her.

names and roles taken directly from a seriously cheesy VHS TV series called Ewoks (which I probably found for a quarter at a garage sale). What I remember most is my daughter’s bright eyes as she tromped around the house after her older brother, who was always kind to her. We used to call them the funnies, and I have a memory of sitting on my dad’s big lap while he folded the newspaper in half, then quarters, so he could read them to me. This would have been on a Sunday, because I remember the strips as being full-color. I still read the daily comics, even though most of them are terrible – tired, unfunny, boring, and retreading the same exact ground for decades on end. Once in a while a strip comes along that’s electrifyingly good –Calvin & Hobbes, Boondocks, Cul de Sac–but they don’t last long, usually because their creators have the courage to cancel them when they’ve run out of steam. So I read out of habit, with no expectation of transcendence. But every once in a while one of them pierces my heart, like today’s Pearls Before Swine, by Stephan Pastis.

We used to call them the funnies, and I have a memory of sitting on my dad’s big lap while he folded the newspaper in half, then quarters, so he could read them to me. This would have been on a Sunday, because I remember the strips as being full-color. I still read the daily comics, even though most of them are terrible – tired, unfunny, boring, and retreading the same exact ground for decades on end. Once in a while a strip comes along that’s electrifyingly good –Calvin & Hobbes, Boondocks, Cul de Sac–but they don’t last long, usually because their creators have the courage to cancel them when they’ve run out of steam. So I read out of habit, with no expectation of transcendence. But every once in a while one of them pierces my heart, like today’s Pearls Before Swine, by Stephan Pastis.