Poem of the Week, by Mike White

A few years ago, from my front porch, I watched an enormous, dark turtle labor its way across Emerson Avenue. It was winter. Snow and ice and slush. A giant turtle? Then the scene resolved itself; the turtle was not a turtle but an old man who had fallen and was trying to crawl to the curb.

A few years ago, from my front porch, I watched an enormous, dark turtle labor its way across Emerson Avenue. It was winter. Snow and ice and slush. A giant turtle? Then the scene resolved itself; the turtle was not a turtle but an old man who had fallen and was trying to crawl to the curb.

I ran out and helped him up and got his walker securely situated. He refused my offer of a ride and carried on down the sidewalk. Sometimes the world turns itself inside out for a few seconds and you stand there entirely confounded. All you can do is wait, and wonder, and let yourself be amazed.

Wind, by Mike White

Not a remarkable wind.

So when the bistro’s patio umbrella

blew suddenly free and pitched

into the middle of the road,

it put a stop to the afternoon.

Something white and amazing

was blocking the way.

A waiter in a clean apron

appeared, not quite

certain, shielding his eyes, wary

of our rumbling engines.

He knelt in the hot road,

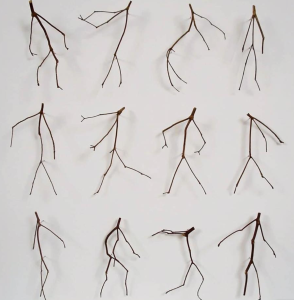

making two figures in white, one

leaning over the sprawled,

broken shape of the other,

creaturely, great-winged,

and now so carefully gathered in.

For more information about Mike White, please check out his website.

My website. My blog. My Facebook page.

Twitter and Instagram: @alisonmcgheewriter

On the surface there’s little in common between Lucille Clifton and me besides the fact that we both grew up in far upstate New York (which, as all upstaters know, is in fact a deep and powerful bond). But ever since I read The Lost Baby Poem in my early twenties, a poem that filled me with so much sorrow and pain and understanding that it felt as if I were somehow embedded in it, she has been a kindred spirit.

On the surface there’s little in common between Lucille Clifton and me besides the fact that we both grew up in far upstate New York (which, as all upstaters know, is in fact a deep and powerful bond). But ever since I read The Lost Baby Poem in my early twenties, a poem that filled me with so much sorrow and pain and understanding that it felt as if I were somehow embedded in it, she has been a kindred spirit.  This past week: the friends in a group discussion admitting they can barely ask what the honorarium is because it feels so selfish. The friend who wonders can I back out of this event in NYC because I just noticed there’s no travel reimbursement and I literally can’t afford it but I can’t stand to let anyone down. The friends who say they know it’s their own fault for feeling ashamed of their bodies and why can’t they just ignore all the ads for liposuction, juvaderm, lip filler, neck filler, breast augmentation, tummy tucks, and vaginal rejuvenation.

This past week: the friends in a group discussion admitting they can barely ask what the honorarium is because it feels so selfish. The friend who wonders can I back out of this event in NYC because I just noticed there’s no travel reimbursement and I literally can’t afford it but I can’t stand to let anyone down. The friends who say they know it’s their own fault for feeling ashamed of their bodies and why can’t they just ignore all the ads for liposuction, juvaderm, lip filler, neck filler, breast augmentation, tummy tucks, and vaginal rejuvenation.

Everything physical, everything specific: the sharp scent of the woods that night in the Adirondacks when the rain drummed down on the canvas tent. The cold clear water that dazzled your body when you plummeted from the rope swing. The softness of the loam under your boots that cold dawn hike in Vermont.

Everything physical, everything specific: the sharp scent of the woods that night in the Adirondacks when the rain drummed down on the canvas tent. The cold clear water that dazzled your body when you plummeted from the rope swing. The softness of the loam under your boots that cold dawn hike in Vermont. Last fall I began getting letters like this from the president, the vice-president, the NRA, anti-abortion organizations. Not my typical mail. Why me? Then it came to me: in August a friend died, a Marine combat veteran, and in his honor I made a donation to the Wounded Warrior project, which must have triggered a hundred conservative mailing lists.

Last fall I began getting letters like this from the president, the vice-president, the NRA, anti-abortion organizations. Not my typical mail. Why me? Then it came to me: in August a friend died, a Marine combat veteran, and in his honor I made a donation to the Wounded Warrior project, which must have triggered a hundred conservative mailing lists. Last summer, driving to Vermont, I detoured past my grandparents’ dairy farm. That’s how I think of it –their farm, on McGhee Hill Road–even though it’s been almost half a century since it changed hands, bought by city dwellers who turned the barn into a house and the house into guest quarters.

Last summer, driving to Vermont, I detoured past my grandparents’ dairy farm. That’s how I think of it –their farm, on McGhee Hill Road–even though it’s been almost half a century since it changed hands, bought by city dwellers who turned the barn into a house and the house into guest quarters.  Who am I? What is my place in this world? How do I stay steady and strong and never stop trying to help the world? Our burning planet. The onrush of artificial intelligence. This heedless erosion of democracy. These are my three biggest panics.

Who am I? What is my place in this world? How do I stay steady and strong and never stop trying to help the world? Our burning planet. The onrush of artificial intelligence. This heedless erosion of democracy. These are my three biggest panics.  Once, when he was about eight, my son looked up at me and said, “Mama, what if we’re all characters in a book, and someone is writing us right now?”

Once, when he was about eight, my son looked up at me and said, “Mama, what if we’re all characters in a book, and someone is writing us right now?”