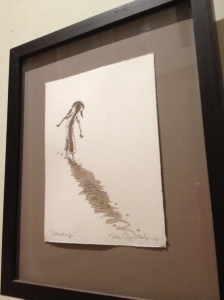

Poem of the Week, by Li-Young Lee

Thirty years ago I stood in a kitchen reading through a letter of complaint sent to a business about one of their products. “Oh my God,” I remember saying. “Whoever wrote this letter is a horrible speller. And the grammar? Jeez!” Then I turned the page over and looked at the signature. And realized that the letter had been written by someone I loved, someone who had worked incredibly hard their whole life long, someone who could always be counted on to help, someone who was right there in the room.

Thirty years ago I stood in a kitchen reading through a letter of complaint sent to a business about one of their products. “Oh my God,” I remember saying. “Whoever wrote this letter is a horrible speller. And the grammar? Jeez!” Then I turned the page over and looked at the signature. And realized that the letter had been written by someone I loved, someone who had worked incredibly hard their whole life long, someone who could always be counted on to help, someone who was right there in the room.

That memory has haunted me ever since. When I think about it, the sensation of shame that flooded through me in that moment, that almost made me fall on my knees, was the beginning of a long slow road that brought me to where I am now, a writer and a teacher of writing who doesn’t care how bad her students’ spelling and grammar are. I am so so sorry, a student wrote me last week, thank you for being so patient and correcting my horrible spelling. All my terrible mistakes must feel like fingernails on a chalkboard to you.

But they don’t. I don’t care anymore about things like that. The surface doesn’t matter to me. Years and years of listening to others’ stories and watching others’ faces when their mistakes are pointed out, when they’re being laughed at, when they smile and smile and smile while their eyes fill with tears, have softened and gentled me. They have turned me into someone who will sit with her laptop propped on her lap and spend whatever time it takes to see through to the golden, glowing sun that shines beneath all those halting sentences.

Persimmons, by Li-Young Lee

In sixth grade Mrs. Walker

slapped the back of my head

and made me stand in the corner

for not knowing the difference

between persimmon and precision.

How to choose

persimmons. This is precision.

Ripe ones are soft and brown-spotted.

Sniff the bottoms. The sweet one

will be fragrant. How to eat:

put the knife away, lay down newspaper.

Peel the skin tenderly, not to tear the meat.

Chew the skin, suck it,

and swallow. Now, eat

the meat of the fruit,

so sweet,

all of it, to the heart.

Donna undresses, her stomach is white.

In the yard, dewy and shivering

with crickets, we lie naked,

face-up, face-down.

I teach her Chinese.

Crickets: chiu chiu. Dew: I’ve forgotten.

Naked: I’ve forgotten.

Ni, wo: you and me.

I part her legs,

remember to tell her

she is beautiful as the moon.

Other words

that got me into trouble were

fight and fright, wren and yarn.

Fight was what I did when I was frightened,

Fright was what I felt when I was fighting.

Wrens are small, plain birds,

yarn is what one knits with.

Wrens are soft as yarn.

My mother made birds out of yarn.

I loved to watch her tie the stuff;

a bird, a rabbit, a wee man.

Mrs. Walker brought a persimmon to class

and cut it up

so everyone could taste

a Chinese apple. Knowing

it wasn’t ripe or sweet, I didn’t eat

but watched the other faces.

My mother said every persimmon has a sun

inside, something golden, glowing,

warm as my face.

Once, in the cellar, I found two wrapped in newspaper,

forgotten and not yet ripe.

I took them and set both on my bedroom windowsill,

where each morning a cardinal

sang, The sun, the sun.

Finally understanding

he was going blind,

my father sat up all one night

waiting for a song, a ghost.

I gave him the persimmons,

swelled, heavy as sadness,

and sweet as love.

This year, in the muddy lighting

of my parents’ cellar, I rummage, looking

for something I lost.

My father sits on the tired, wooden stairs,

black cane between his knees,

hand over hand, gripping the handle.

He’s so happy that I’ve come home.

I ask how his eyes are, a stupid question.

All gone, he answers.

Under some blankets, I find a box.

Inside the box I find three scrolls.

I sit beside him and untie

three paintings by my father:

Hibiscus leaf and a white flower.

Two cats preening.

Two persimmons, so full they want to drop from the cloth.

He raises both hands to touch the cloth,

asks, Which is this?

This is persimmons, Father.

Oh, the feel of the wolftail on the silk,

the strength, the tense

precision in the wrist.

I painted them hundreds of times

eyes closed. These I painted blind.

Some things never leave a person:

scent of the hair of one you love,

the texture of persimmons,

in your palm, the ripe weight.

A house I used to live in was filled with a dark and ominous energy that I felt every time I approached the front door. When I dreamed, dark birds hovered silently in the air around me, landing on my shoulders and head. The dark birds wanted me — they wanted me dead. I lived in a state of permanent exhaustion, surrounded by the forces of darkness.

A house I used to live in was filled with a dark and ominous energy that I felt every time I approached the front door. When I dreamed, dark birds hovered silently in the air around me, landing on my shoulders and head. The dark birds wanted me — they wanted me dead. I lived in a state of permanent exhaustion, surrounded by the forces of darkness.  Hey there, elected employees, thanks for an especially sickening week. Proud of yourselves and your ongoing attempts to destroy our democracy?

Hey there, elected employees, thanks for an especially sickening week. Proud of yourselves and your ongoing attempts to destroy our democracy?  My new novel

My new novel  This semester I taught a class about creative writers, identity and race. Forty students of wildly different backgrounds, ethnicities, religions and race sat in a huge square in an underground room in a building next to the train tracks midway between Minneapolis and St. Paul. We were strangers to each other. On the first day of class, I gave them a writing-from-life prompt. They wrote quickly and in silence, then some of them read their pieces aloud. The class is over now, and in their final paper, one student wrote of that first day, back in August,

This semester I taught a class about creative writers, identity and race. Forty students of wildly different backgrounds, ethnicities, religions and race sat in a huge square in an underground room in a building next to the train tracks midway between Minneapolis and St. Paul. We were strangers to each other. On the first day of class, I gave them a writing-from-life prompt. They wrote quickly and in silence, then some of them read their pieces aloud. The class is over now, and in their final paper, one student wrote of that first day, back in August,  When my children were tiny they went to a neighborhood preschool two or three mornings a week. It was a gentle place, taught by lovely teachers who never got upset if a glass of milk was toppled or if someone broke a crayon. There was a dress-up corner, a story-time corner, a Lego corner. In nice weather the kids went outside and worked and played in a flower garden the school had created along a biking and walking path.

When my children were tiny they went to a neighborhood preschool two or three mornings a week. It was a gentle place, taught by lovely teachers who never got upset if a glass of milk was toppled or if someone broke a crayon. There was a dress-up corner, a story-time corner, a Lego corner. In nice weather the kids went outside and worked and played in a flower garden the school had created along a biking and walking path.  When my son was a year and a half he came down with a stomach flu. After a couple of days the vomiting and diarrhea had calmed down, but he was quiet and listless. I wasn’t terribly worried but something told me to take him to the clinic, so I did. His doctor examined him in the little bright-lit room the same way I had grown used to, with calm and gentleness. I trusted this doctor completely and instinctively the minute I met him. He was older, small and lean, with wise eyes.

When my son was a year and a half he came down with a stomach flu. After a couple of days the vomiting and diarrhea had calmed down, but he was quiet and listless. I wasn’t terribly worried but something told me to take him to the clinic, so I did. His doctor examined him in the little bright-lit room the same way I had grown used to, with calm and gentleness. I trusted this doctor completely and instinctively the minute I met him. He was older, small and lean, with wise eyes.  After a reading from my new novel

After a reading from my new novel