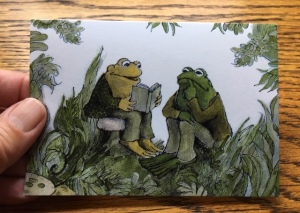

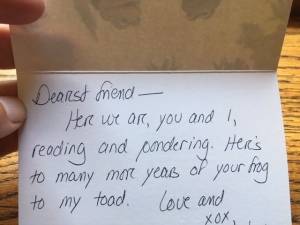

An upstairs cupboard in my house holds three cardboard boxes filled with letters from my friend Garvin Wong. For the eighteen years of our friendship, beginning when I was in my thirties and he in his fifties, we exchanged hundreds and hundreds of letters. His were typed on an old typewriter that could have used a new ribbon, mine were printed out from computers, first by dot-matrix and then on lasers.

An upstairs cupboard in my house holds three cardboard boxes filled with letters from my friend Garvin Wong. For the eighteen years of our friendship, beginning when I was in my thirties and he in his fifties, we exchanged hundreds and hundreds of letters. His were typed on an old typewriter that could have used a new ribbon, mine were printed out from computers, first by dot-matrix and then on lasers.

Before I was a published writer, frustrated that no one seemed to want to read what I wrote, I used to print out my stories, copy them at Kinko’s, and then leave them lying around town in laundromats and coffee shops. One of my sisters gave one of them to a late-night talk radio host in Manhattan who read the story on air and then gave his listeners my post office box address. The box was soon flooded with letters, one of them from Garvin. Something about that first letter, typed on his ancient typewriter, moved me, and I wrote back.

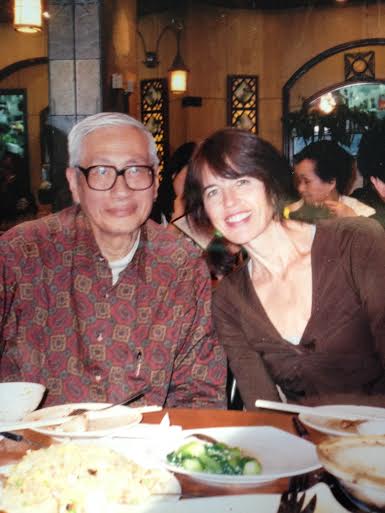

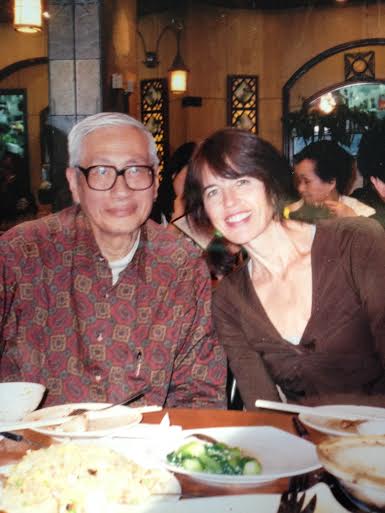

Garvin was a quarter-century older than me. He lived his entire life in Queens, most of it in the house he grew up in and where he cared for his parents until they died. He was a dentist and he worked in his uncle’s Chinatown dental office. He also volunteered at a free dental clinic and worked at a pediatric dental clinic. He loved children. When he found out I had three small children, he began sending them gifts: T-shirts, little trinkets he thought they might like, special Chinese candies. Each year on the lunar New Year, a box of red-bean paste cookies would arrive. He knew how much I love ginger, and every few months ginger, in multiple forms, showed up on the doorstep: ginger candy, dried ginger, ginger cookies, ginger tea. Garvin was a native English speaker but he also spoke Cantonese, and I understand rudimentary Mandarin. We used to celebrate our love of Chinese by sprinkling it throughout our notes, the characters for love, peace and ginger chief among them.

Years went by. Garvin met my whole family and began to spend Thanksgiving with my sister Holly in New Jersey, where every year he brought his own carving knife to her house, carrying it on the subway, so that he could carve the turkey. It took him an hour, so precise was he, and she nicknamed him “Carvin’ Garvin.” Whenever I was in New York, he would arrange an elaborate meal in Chinatown, complete with handmade menus full of punned names for each course (he loved puns and wordplay in general) and a theme for each dinner. Afterward we would wander around Chinatown, stopping here and there so that he could fill his backpack with fresh fruit and groceries. Garvin always wore a backpack, and the backpack was usually filled with empty plastic containers so that he could order lots of food and take the leftovers home for the rest of the week.

More years went by. In one of his letters, he mentioned that someone had offered him a seat on the subway: “I’m getting on.” In another, he said that he thought of himself as my adoptive, second father. After he came to visit us –the first time he had been on a plane in 37 years– he wrote to say that he had seen a pretty flight attendant in the airport and “It makes me wish I were 20 years younger.”

My letters became more frequent; he was old now, and his twice-weekly trips from Queens to Chinatown were harder and harder. He wrote of resting at the top and bottom of the subway steps, and how difficult it was to do things like mop up his basement, which tended to flood. He wrote of how his neighbor Foon watched out for him and helped him with heavy packages.

Then came the day when he called from the hospital to say that he had fallen in his home, and how Foon had found him after almost two days. That he was injured and would be in rehab for quite a time before he could return home. My sister and I got him an iPad so that we could Facetime. We found a wonderful eldercare specialist who helped coordinate care and visits. But in the hospital his never-diagnosed or treated diabetes came to light, and then his foot was amputated, and everything went downhill.

I sent him a letter in which I recounted our life together, the many years we had known each other, the small adventures we had had, the love and caring he had shown me and my family. I told him that if and when he was ready to go, he should know that my love surrounded him. His heart stopped beating a day later. Someone else decided to resuscitate him, but he died alone in the ICU the next night. I was not with him. I wish I had been with him. It haunts me that he died without me.

Garvin’s death brought a sense of loss that I thought I was ready for, but I wasn’t. In the five years since his death, I have talked to him in my mind. All the questions I never asked him, out of respect or because I hadn’t thought of them: Had he ever been in love? Had he, with his liveliness around children, the way he lit up in their presence, ever wanted to be a father? I remembered his last visit to us, when he was sitting across the kitchen table from me and looked visibly tired and old, and it came to me that it was possible, maybe probable, he had never held someone’s hand. That no one had ever touched him that way. I reached across the table and picked his hand up and held it in my own. He said nothing. Neither did I.

Maybe he was much lonelier than I ever knew. Maybe he wasn’t. It troubles me that I don’t know the answers to these questions, and it troubles me that I never asked. It troubles me that even now, in the wake of my loss, I still hold questions inside me for and about the living people I most love in the world. How well can we ever truly know each other? What do we hold in our hearts that we won’t, or don’t, talk about?

In his last months, Garvin told me he had been talking to his father in his mind, and asking for advice. That, unlike his mother, his father had been a comfort to him, a gentle, kind man who always listened to his painfully shy son. Who loved him as he was. This beautiful poem below brought Garvin back to me, along with his father, who died before I ever met his son.

My Father, Long Dead, by Eileen Sheehan

My father, long dead,

has become air

Become scent

of pipe smoke, of turf smoke, of resin

Become light

and shade on the river

Become foxglove,

buttercup, tree bark

Become corncrake

lost from the meadow

Become silence,

places of calm

Become badger at dusk,

deer in the thicket

Become grass

on the road to the castle

Become mist

on the turret

Become dark-haired hero in a story

written by a dark-haired child

For more information on Eileen Sheehan, please click here.

Once, at a Twins play-off game, I sat next to an older couple. They opened a tote and pulled out sandwiches wrapped in waxed paper, peeled carrots, small bags of grapes, and cookies. Dinner, packed at home and brought to the game. There was something about this couple I loved.

Once, at a Twins play-off game, I sat next to an older couple. They opened a tote and pulled out sandwiches wrapped in waxed paper, peeled carrots, small bags of grapes, and cookies. Dinner, packed at home and brought to the game. There was something about this couple I loved. That woman sitting on the bar stool with a martini and a magazine, or alone on her couch spinning imaginary people into books, or flying solo around the world: she is me. But won’t you be lonely? is a question I’ve heard a lot in my life, and I don’t know how to answer it, because isn’t everyone, somewhere inside themselves, lonely?

That woman sitting on the bar stool with a martini and a magazine, or alone on her couch spinning imaginary people into books, or flying solo around the world: she is me. But won’t you be lonely? is a question I’ve heard a lot in my life, and I don’t know how to answer it, because isn’t everyone, somewhere inside themselves, lonely?  Last weekend I watched as seven brothers and their sister gathered around a polished casket that held the body of their mother, a woman loved by all. The night before, the siblings had stayed up late laughing and telling stories of how she used to shoo them up to bed with a broom, how she taught Phys Ed for thirty-nine years while delivering papers before dawn and working in the family print shop at night, how she loved wine (with a few ice cubes) and fast-pitch softball and mint chocolate chip ice cream and the Minnesota Twins.

Last weekend I watched as seven brothers and their sister gathered around a polished casket that held the body of their mother, a woman loved by all. The night before, the siblings had stayed up late laughing and telling stories of how she used to shoo them up to bed with a broom, how she taught Phys Ed for thirty-nine years while delivering papers before dawn and working in the family print shop at night, how she loved wine (with a few ice cubes) and fast-pitch softball and mint chocolate chip ice cream and the Minnesota Twins. One of my best friends and I sat on my porch last night talking about how our lives might have been different. What if I’d made myself deal with that suicide instead of trying to escape the pain? What if she’d said yes to that job? What if I’d stayed in New England? What if we’d mothered our children differently?

One of my best friends and I sat on my porch last night talking about how our lives might have been different. What if I’d made myself deal with that suicide instead of trying to escape the pain? What if she’d said yes to that job? What if I’d stayed in New England? What if we’d mothered our children differently?

Two lovely Japanese maple trees in a front yard one block south are symmetrically planted amid cement squares filled with small white stones. For eight years I walked past this house every day, so I could admire the way the owners, whom I always pictured as two calm men, swept the leaves and raked the stones into perfect, weed-free squares. Looking at this yard calmed my spirit. A few years ago the house was sold, and since then it has been reclaimed by wildness.

Two lovely Japanese maple trees in a front yard one block south are symmetrically planted amid cement squares filled with small white stones. For eight years I walked past this house every day, so I could admire the way the owners, whom I always pictured as two calm men, swept the leaves and raked the stones into perfect, weed-free squares. Looking at this yard calmed my spirit. A few years ago the house was sold, and since then it has been reclaimed by wildness.

When I was nine my father brought me a huge, bright-green, horned bug from our garden: Look! You can bring it in to school for the bug project! When he turned away I placed some tomatoes on top of the bug, and later had to admit in shame that I had ‘accidentally’ crushed it. Alison! What the hell were you thinking?

When I was nine my father brought me a huge, bright-green, horned bug from our garden: Look! You can bring it in to school for the bug project! When he turned away I placed some tomatoes on top of the bug, and later had to admit in shame that I had ‘accidentally’ crushed it. Alison! What the hell were you thinking?  Last night I wandered around a downtown park filled with strange, beautiful, confounding, mesmerizing art: dancers, sculptors, glass blowers, painters, musicians, weavers, poets, mask makers. It was nightfall in the city. Skyscrapers glowed around the periphery of the park, light rail trains glided by, and storm clouds gathered and dispersed overhead. At one point I sat on the base of a sculpture and took it all in, the voices and laughter and absorption on the faces of the crowd.

Last night I wandered around a downtown park filled with strange, beautiful, confounding, mesmerizing art: dancers, sculptors, glass blowers, painters, musicians, weavers, poets, mask makers. It was nightfall in the city. Skyscrapers glowed around the periphery of the park, light rail trains glided by, and storm clouds gathered and dispersed overhead. At one point I sat on the base of a sculpture and took it all in, the voices and laughter and absorption on the faces of the crowd.  Old friend, it has been decades since that last summer before college, the last time I ever lived at home. But when I return to visit my parents and drive by the street where you once lived, I remember you. I remember rain on a canvas roof, darkness all around, the silent sleeping breath of other friends. I remember how surprised I was that someone wanted to kiss me –me?–and I remember your gentleness. Let me tell you now that you were the one who first showed me how touch could open up a new world. At seventeen I could not have known how the memory of that fleeting sweetness would sustain me in future dark times. This achingly beautiful poem brought back the memory of you.

Old friend, it has been decades since that last summer before college, the last time I ever lived at home. But when I return to visit my parents and drive by the street where you once lived, I remember you. I remember rain on a canvas roof, darkness all around, the silent sleeping breath of other friends. I remember how surprised I was that someone wanted to kiss me –me?–and I remember your gentleness. Let me tell you now that you were the one who first showed me how touch could open up a new world. At seventeen I could not have known how the memory of that fleeting sweetness would sustain me in future dark times. This achingly beautiful poem brought back the memory of you.  It was Bring Your Parent to Lunch Day at elementary school and I was sitting at a cafeteria table with my daughter. She was born between her brother and sister – there hadn’t and wouldn’t be a stretch of time when it was just the two of us in the house – and she was quietly thrilled at my presence.

It was Bring Your Parent to Lunch Day at elementary school and I was sitting at a cafeteria table with my daughter. She was born between her brother and sister – there hadn’t and wouldn’t be a stretch of time when it was just the two of us in the house – and she was quietly thrilled at my presence. An upstairs cupboard in my house holds three cardboard boxes filled with letters from my friend Garvin Wong. For the eighteen years of our friendship, beginning when I was in my thirties and he in his fifties, we exchanged hundreds and hundreds of letters. His were typed on an old typewriter that could have used a new ribbon, mine were printed out from computers, first by dot-matrix and then on lasers.

An upstairs cupboard in my house holds three cardboard boxes filled with letters from my friend Garvin Wong. For the eighteen years of our friendship, beginning when I was in my thirties and he in his fifties, we exchanged hundreds and hundreds of letters. His were typed on an old typewriter that could have used a new ribbon, mine were printed out from computers, first by dot-matrix and then on lasers.